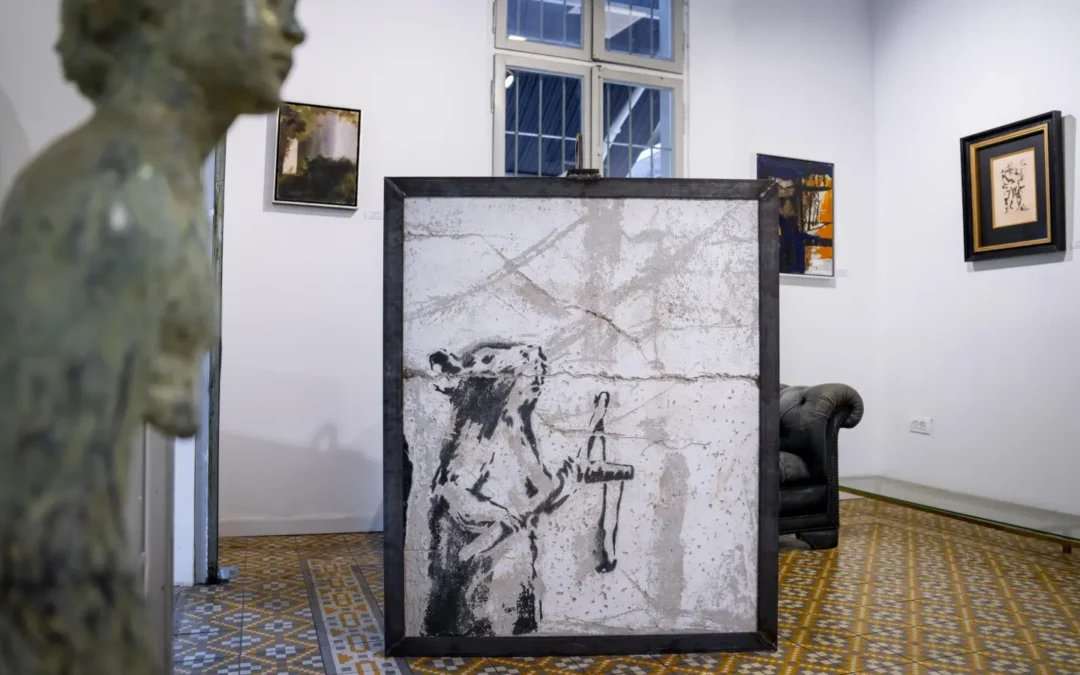

A Banksy masterpiece once sprayed onto a concrete wall in the occupied West Bank has intriguingly appeared in an upscale art gallery in Tel Aviv, situated an hour’s journey but seemingly a world apart from its original location. The relocation of this artwork, depicting a rat armed with a slingshot—likely a critique of the Israeli occupation—sparks debate over the ethical ramifications of moving art from occupied territories and showcasing politically potent pieces in vastly different contexts than their origins.

Originally placed near Israel’s separation barrier in Bethlehem around 2007, the piece is among several that utilized Banksy’s signature blend of absurdity and dystopian themes to challenge the enduring occupation over territories claimed by Palestinians for a prospective state. Presently, it is displayed at the Urban Gallery, amidst Tel Aviv’s bustling financial sector of modern glass and steel structures.

Koby Abergel, an Israeli art dealer who acquired the painting, likened its story to “David and Goliath,” without delving into specifics. He emphasized that the gallery’s role is to exhibit the artwork, leaving interpretations up to the audience.

Although the Associated Press has not independently verified the artwork’s authenticity, Abergel points to the concrete’s distinctive marks as evidence of its genuineness, matching images on the artist’s website.

The 900-pound slab’s secretive transport from the West Bank to Tel Aviv involved bypassing Israel’s complex barrier and military checkpoints—a daily ordeal for Palestinians and a frequent target of Banksy’s satire.

Abergel disclosed purchasing the slab from a Palestinian contact in Bethlehem but did not reveal the price or the seller’s identity, maintaining the transaction’s legality.

The artwork, once part of an abandoned Israeli military post and subsequently vandalized, was preserved by Palestinian residents until its recent unveiling. Abergel detailed the intricate negotiation and restoration efforts to present Banksy’s work anew in Tel Aviv, amidst contemporary art on a decorative tile floor, transported by crane due to its immense weight.

Israel’s tight control over the West Bank raises questions regarding the legality of such movements under international treaties, such as the 1954 Hague Convention, which Israel has signed, dictating the protection of cultural property in occupied territories.

Palestinian authorities have condemned the artwork’s removal as theft, emphasizing its significance to Bethlehem and Palestinian heritage. Meanwhile, the Israeli military and civilian coordination bodies claim no knowledge of the artwork or its relocation.

Banksy’s work, renowned for its poignant critiques on conflict zones, including several pieces in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, continues to provoke discussion. His involvement, or lack thereof, in the relocation remains unconfirmed, as does the artwork’s future.

As debates swirl around the ethics of its relocation, Abergel suggests that the artwork’s new setting in Tel Aviv serves to amplify Banksy’s messages to a wider audience, albeit in a context far removed from its original, charged backdrop.